Travels in China

July 2005

Shanghai

My trip to China began with a series of weird surprises. First there was the news that the summer camp at which I was supposed to be working as an English teacher was being cancelled. I decided to fly to China anyway, along with about thirty-five other British and Irish students who were in the same position. Then, as I was preparing to fly from Scotland to London on my way to Shanghai, came the news that, for a third time, my choice of destination had coincided with al-Qaeda's. (I embarked on a round-the-world trip that included the USA a few days before 9/11, and I also happened to be in Madrid in the aftermath of the train bombings there.) Fortunately, while much of London transport came to a terrorized halt, Heathrow airport continued to run more-or-less normally, although Terminal 2 was briefly evacuated due to a bomb scare, and one or two people had to get their parents to drive them the hundreds of miles to Heathrow from Edinburgh because of the lack of public transport to the airport!

Landing at the wrong airport in Shanghai was the third surprise. China Eastern Airlines never explained in English why they decided, at the last minute, to hop over Pudong airport and take us instead to Hongqiao, on the other side of the city; it may have been due to weather. It was early evening and Shanghai was sweltering in a hot, electric haze, with sporadic flickers of lightning playing amongst the skyscrapers. Many of the buildings were only dimly lit: when summer temperatures rise into the high 30s (90-100°F) and a city of thirteen million turns up its air conditioning, electricity supplies run short. The cityscape looked vast and alien; it resembled a scene from a science fiction movie.

I shared a hotel room with Ben, my flatmate from Edinburgh, who had also planned to come to work as an English teacher, and was determined to find a job in China in spite of the cancellation of the summer camps. To achieve this he embraced the Chinese tradition of guanxi (making the most of your network of contacts), and enlisted the help of his brother's friend's mother's friend's friend, a Chinese journalism student named Toni, who decided that the attempts of a Northern Irish guy to find work in China would make an excellent subject for a short documentary film. Ben thus found himself met at the airport by an enthusiastic Chinese girl waving a video camera, and I found myself the co-star in Toni's documentary. To add some drama to the film, Toni wanted to film me making a bet with Ben that he couldn't find a job within three days. I was happy to be involved in the enterprise, because having someone around who spoke Chinese made our first few hours in Shanghai a lot easier. If it hadn't been for Toni's help at dinner that night, we would probably have been reduced to performing pig and chicken impressions in the restaurant in order to communicate what we wanted. With Toni's help, we ordered a mixture of local specialties, including jellyfish and 'giant frog'. The jellyfish (which was heavily fried, like most Chinese food) tasted surprisingly good, although the fried lumps of squidgy frog meat were less than appetizing.

The next day, Ben and I went sightseeing, accompanied by Toni, who filmed Ben's reactions to the strange country and the occasional pessimistic remark from me about Ben's chances of finding work here. We crossed the river via the Bund Sightseeing Tunnel, a strong contender for the title of World's Most Psychedelic Subway. During the short mini-train ride under the river, we were bombarded with array of flashing, strobing, circling and flickering lights (accompanied by suitably zany sound effects) that seemed purposefully designed to bring to the surface any hidden neurological problem that passengers might be afflicted with. On the eastern side of the river, we visited the Oriental Pearl Tower, from which we could see grey high-rise buildings stretching in every direction into a polluted mist.

Ben and Toni left Shanghai that evening, and I spent the next couple of days enjoying the city's attractions with some of the other would-be English teachers. Young British tourists are a nocturnal species, and sleepy days of half-arsed sightseeing were followed by long nights of loud entertainment and cheap Tsingtao beer. It was a shamelessly Western way of behaving, but Shanghai was a shamelessly Westernised place. On the corner of the historic People's Park in the centre of the city, there now stood a Starbucks. Nearby were KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, and several McDonalds. Less than a century after the Chinese Communist Party was founded here, Shanghai has evolved into one of the most spectacularly capitalist cities on Earth. So far, however, only a rich minority of the city's inhabitants could afford the greasy delights of Western fast food. Though its prices were (if anything) slightly cheaper than those in Britain, the Pizza Hut overlooking People's Park is treated by the Chinese as a plush, expensive restaurant, and has an atmosphere to match, with luminously well-polished décor and the kind of service for which you would pay hundreds of pounds in London. In the 'restroom' (no filthy 'toilet' here) there was an attendant to turn the tap on and off, and ice cubes in the urinals for ultimate freshness.

A hazy moonrise behind Shanghai's futuristic skyline

One night, after spending a while trying to blag our way to the tops of random tall buildings in search of good views (we got to the top of a couple, but saw only corridors), we came across a karaoke bar. Here karaoke was done in a different (and far less embarrassing) way than in Western bars: groups of friends are locked in private soundproof rooms with a karaoke machine, a pair of microphones, a couple of tambourines, and a plentiful supply of cheap alcohol. It was hilarious, and we stayed until our throats were sore and our ears were ringing.

Hohhot

Though Shanghai was fun, spending several days there doing little but drinking beer and hanging out with other Brits seemed like a waste of my trip to China. On the third day, therefore, I went into a travel agent, handed over some money and a scrap of paper on which I'd painstakingly copied down a place name and date in Chinese characters, and came away with an airline ticket. One of the other Brits, an Oxford student named Louise, decided at the last minute to come with me. This was a relief, because her attempts at speaking Chinese were a lot better than mine.

Two days and several hundred miles later, we found ourselves in Hohhot, capital of Inner Mongolia. Curiously, Inner Mongolia does not belong to the country of Mongolia - it's a province of China - and nor is it the innermost part of the region as seen on a map. However, Mongolian people and traditions are very much in evidence there, and many signs are adorned with outlandish vertical Mongolian script (whose words look like spiky dangling caterpillars) alongside Chinese symbols. Latin letters are a rare sight here. Few Westerners come to Hohhot, and two pale-skinned, blue-eyed tourists walking down the street attract disconcerting stares from passers-by.

In a country as large and populous as China, even the smaller dots on the map can be sizeable places. Hohhot was a city of a million people, with tall concrete buildings and a grinding throng of people, cars and bicycles making their way haphazardly along vast, eight-lane boulevards. The crossings on these roads were largely ignored by pedestrians and motorists alike, and crossing the road was a matter of walking out into the traffic and trusting the vehicles to swerve around you. In the city centre were Western-style shopping malls. McDonald's, KFC and Pizza Hut were all here. At night, a profusion of coloured lighting gave the city a Las Vegas-like quality; one of the main boulevards was decorated with columns of coloured lights in the shape of DNA helices. In a big plaza at the heart of the city was a nightly fountain display that attracts huge crowds.

The one person we met in Hohhot who spoke fluent English was Edward (that, at least, was his "English name"), a Chinese university student, who noticed us watching the fountains and spotted an opportunity to practise his English. We went for a drink, and chatted about student life in our respective countries. Upon hearing that we were from England, he responded in the same way as many foreigners: "ah, same place as David Beckham". It is sad that this man has now become the most widely-known symbol of Englishness across the world.

The other Englishman who was well known here, Edward told us, was Tony Blair, who was unpopular in China (as in most other parts of the world) because of the Iraq war. I reflexively responded that I'd never voted for Blair. Here in China, nobody votes for their political leaders, Edward reminded me. However, he believed that having a one-party state was good, for the time being at least, because it provided the strong leadership that China needed to develop and modernise. It was hard to tell if this was his genuine opinion (it's only sixteen years since students like Edward were gunned down around Tiananmen Square for expressing a contrary point of view), but it may well have been. Many urban Chinese were clearly doing well under their resolutely-undemocratic regime. The Chinese appeared to take the attitude that democracy may eventually come to their country - along with all the other Western luxuries that were starting to appear, like McDonald's and Starbucks - but that the country can manage fine without it. They are probably right.

Xilamuren

After a day in Hohhot, we headed north, on a tour to the Inner Mongolian grasslands. It's amazing how many distant regions of the world I can visit and be reminded of Scotland. From a distance, the rolling, brownish-green steppes, dotted with pale villages and dissected in places by roads and telephone wires, resembled the bleak moors of the Scottish Highlands. There was one big difference, however: the landscape here was dusty and arid, and the summer sun was baking. The plains were grazed by horses, cattle and sheep, and big brown crickets scuttled through the vegetation. Some patches were carpeted with purple-flowered thyme, which gave off a faint herbal fragrance as you walked across.

Out on the open plains, Louise and I attempted to go horse riding. Unfortunately, as soon as we were on their backs, our horses decided to go and join another group of horses, half a mile away, and realised that we weren't capable of stopping them. All we could do was cling on desperately as they cantered away across the steppes, kicking up a trail of dust behind them. The horses eventually reached the place they wanted to be, where some friendly Mongolian herdsmen helped us to the ground. Badly shaken, we were reluctantly persuaded back into the saddle, and from then on were led by a rope at walking pace, like toddlers taking their first pony ride.

We spent the night at the nearby settlement of Xilamuren, sleeping on mattresses on the floor of a yurt, a version of the round prehistoric-style huts traditionally used by nomads on the plains. The yurts at Xilamuren were modern constructions, with concrete bases, carpeted floors, electric lights, and walls made from heavily-insulated layers of synthetic fabric rather than animal hides. Nonetheless, they were attractively decorated and had a very traditional feel to them. Xilamuren is a major tourist centre, and here we had the opportunity to visit a Tibetan temple (Mongolia and Tibet have strong cultural affinities, despite being at opposite sides of a vast intervening country) and watch Mongolian spectacles such as horse racing, wrestling and dancing.

In a big communal yurt, we enjoyed a traditional Mongolian dinner whilst listening to beautiful local music, which included some incredible guttural singing from a man with a voice like a didgeridoo. Later in the evening, whilst standing outside admiring the clear, star-speckled sky, we heard modern dance music blaring from a nearby building. We went to investigate, and found several of the Mongolian dancers and musicians - now changed into trendy Western clothes - making the most of the venue's dance floor and sound system. They beckoned us to join them, and Louise and I became involved in an impromptu Mongolian disco. We discovered, after strenuous attempts at communication (they spoke hardly any English, we spoke no Mongolian, and nobody spoke much Chinese), that they came from Ulan-Bator (the Outer Mongolian capital), that they were about our age, and that during term-time they were students like us.

The next morning, we got up early and climbed a nearby hill to watch the sunrise beaming across the steppes, before returning to Hohhot.

Beijing

On the night that the sixth Harry Potter book was released, Louise and I were travelling by a mode of transport known to most Brits only through the works of J K Rowling: a night bus, filled with beds rather than seats, in which passengers attempted with difficulty to sleep as the bus swerved and juddered in the direction of the capital city. Cramped into tiny bunks jammed with passengers sweating profusely in the heat, the ride was a less-than-magical experience.

Beijing - the capital of what will, on present trends, one day become the most powerful nation on Earth - was a monstrous place. In population terms it was no larger than Shanghai, but Beijing (like that other great imperial capital, London) was dominated not by dense skyscrapers but by low, historic buildings that spread out across a vast area. Beijing municipality is the size of Belgium, and even the city centre covers an area several miles square.

Unlike Hohhot, Beijing was well geared up to receive Western tourists. This had its advantages - there were good youth hostels, for example, and many restaurants had English-language menus. However, the abundance of visitors also created an abundance of people adept at harassing, exploiting and robbing them. My camera was stolen as I was jostled in a crowd, and in order to obtain a loss report for insurance purposes, I had to spend a fraught afternoon in the imposing grey offices of the Public Security Bureau - the Chinese police. I was apprehensive about my encounter with this arm of China's notorious authoritarian state, yet the policemen were friendly and patient as I thumbed through my well-used Mandarin phrasebook, attempting to explain what had happened and repeatedly returning to the phrase "Does anyone here speak English?". Eventually an English-speaking policeman was found and I obtained a report with little fuss.

Beijing had many sights, but the city's size made getting from place to place a hassle. Walking was unpleasant in the heat and the crowds, and although bikes could easily be hired, I was frightened to cycle on Chinese roads. The locals drove as though they were in a computer game and had several lives to spare. The bus network was confusing, and the metro network was limited. Pedicabs (cycle taxis) abounded, but behaved like sharks, circling their pale-skinned, tired-looking victims incessantly until they got their fill of juicy cash. Ordinary taxis were cheap, especially when travelling in a group, but many of their drivers were astonishingly incompetent, unable to find obvious destinations even when shown a map or given written directions in Chinese.

The language barrier was by far the most challenging aspect of visiting China. The hundred million Chinese people who are meant to be learning English kept themselves well hidden, and communication often consisted of gestures, pointing at phrasebooks, or drawing things on scraps of paper. (Some exchanges turned into elaborate games of charades or Pictionary.) Our inability to even write down words or place names in Chinese meant that even having a pen and paper didn't always help. It's hard to travel in a country in which you are not only unable to speak the language, but are utterly illiterate. Even where the Chinese attempted to help Western visitors by producing signs in English, translation was frequently necessary. It took us a while to work out that the sign in a hotel lobby inviting us to "Go second for have eat" was directing us to the restaurant on the second floor. Other examples of 'Chinglish' were simply amusing. A sign at the entrance to a Beijing parlkland invited visitors to "admire the grotesque rockeries", which were "in a natural state of disorder". Another implored visitors to "buy a ticket consciously" - instead of buying tickets in our sleep, presumably. Those who did have a problem with sleepwalking should have been advised to go and see a particular Hollywood movie (I forget which one) for which I watched a trailer on Chinese television. The trailer's English subtitles proclaimed that the movie would not only entertain you, but would enrich your mind and "cure your sycological [sic] diseases". Powerful stuff.

A counter in Tiananmen Square proclaimed that there were only 1116 days left until Beijing hosts the Olympic Games. However, if the city doesn't succeed in its attempts to improve air quality before the 2008 Olympics, it will appear on foreigners' TV screens as a very grey and dirty showcase for twenty-first century China. At this time of year a polluted haze hangs over the city, which gives the alleyways and parklands an intriguing mystical quality, but spoils the view of Beijing's more impressive sights. At times it could be difficult to see one side of Tiananmen Square from the other because of the smog.

Beijing's 'Forbidden' City, fading into the smog

Together with many of the other Brits with whom I was in Shanghai, I stayed at a youth hostel nestled in one of Beijing's famous hutong - the mazes of low, historic alleyways that nestle in between enormous, Communist-planned main roads. The hutong were intriguing places to explore, and provided a real insight into everyday Chinese city life. Passing the tiny dwellings we caught glimpses of families going about their daily chores, whilst old men sat at the sides of the alleys smoking and playing board games. A cornucopia of shops and stalls sold everything from beer and watermelons to live birds and crickets.

One day I joined the thousands of people queuing in a line around Tiananmen Square to visit the immense mausoleum of Chairman Mao, the figure who did so much (for better or worse) to shape modern China, and whose immense portrait still hung from the red gate at the northern end of the square. For a few hours each morning, Mao's preserved body was removed from its refrigerator and put on display for visitors to pay their respects. Many Chinese bought bunches of flowers, which they deposited on a trolley at the entrance to the mausoleum. From here the flowers were collected, returned to the flower stall outside and reused. After queuing for an hour visitors got only a few seconds to take in the sight of the famous man, whose surprisingly-small body reposed behind two layers of glass. His body looked like a waxwork model (many people suspected that it was a waxwork model). From the respectful silence of the mausoleum, the queue filed out into the smoggy daylight of Tiananmen Square, past lines of souvenir stands exploiting the old man's memory in a somewhat un-Communist way.

Another morbid tourist attraction was Beijing's Natural History Museum, which contained - alongside the usual stuffed animals and dinosaur skeletons - the gruesomely intriguing spectacle of partially-dissected human corpses preserved in formaldehyde.

At the historic centre of Beijing is the Forbidden City, the enormous palace complex in which Chinese emperors once lived in splendid isolation from the proletarian squalor outside. Now that the emperors were gone, the 'Forbidden' City had opened up its gates to anyone willing to pay the entrance fee, and the place had been overrun by more outsiders than almost any other spot in China. (The irony of this appeared to have been lost on the Chinese tourist authorities.) The immense, red halls and gateways of the Forbidden City were imposing and impressive, but not beautiful. Much of the complex remained closed off (and covered with ugly scaffolding), corralling the thousands of visitors into a few hot and well-trampled courtyards. It was such a hypertouristed place that the tourists themselves had become part of the attraction: on several occasions we were approached by Chinese families who wanted to take photos of themselves standing beside groups of Western tourists!

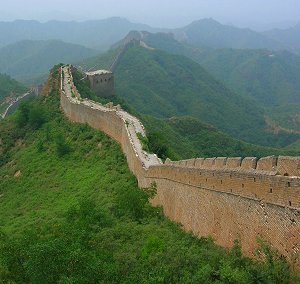

The other mega-attraction in this part of China is, of course, the Great Wall. Many people have compiled lists of places that people should aspire to see before they die, and almost every such list includes the Great Wall of China. Though only short fragments of the ancient Wall survive - and, contrary to popular belief, it could never be seen from the Moon - it remains an extremely impressive structure. The Great Wall was never much good at keeping out invading Mongol hordes, but it did provide a convenient roadway for soldiers moving through difficult terrain. Our tour group hiked six miles (10 km) along a relatively little-visited section of the Wall, where it traverses steeply-sloping peaks like a giant staircase undulating through the mountains. Frequent watch towers provided a shady respite from the heat, which was intense, in spite of the breezes blowing across the Wall. The views down the mountains on either side were dramatic, and in places the air was filled with dragonflies. (Appropriately, these insects are abundant in China.)

The Great Wall running along the mountaintops

My last day in Beijing was one of the hottest I've ever experienced, anywhere. With temperatures soaring into the 40s (about 110°F), walking around the city was like wading through a hot bath. We tried to escape from the heat in the way that the emperors used to, by spending an afternoon at the Summer Palace, a breezy lakeside park a few miles of the city centre. With crowds of sweaty visitors thronging the gardens, and pollution hanging over the lake, the place is not quite the tranquil retreat it was in the emperor's day, but it was at least cooler than the city streets.

Pingyao

That evening, Louise and I got an overnight train to Pingyao, together with Sarah, another British student. Rail travel is popular in China (no less than ten million Chinese are estimated to be on trains at any given time), and the main railway stations of Chinese cities were colossal places. Beijing West is reputedly the largest station in Asia, and resembled an international airport, complete with numbered departure lounges and X-ray screening of passengers' luggage at the entrance. The trains, too, were leviathans - gigantic, Soviet-inspired metal hulks designed for transporting very large numbers of people across very large distances. Inside, the trains were surprisingly clean and comfortable, although on this journey we were only able to buy 'hard seat' tickets - the lowest class of rail travel. The seats were not actually hard, but they were cramped and shaped in such a way as to make sleeping in them virtually impossible. Many passengers resorted to spreading out newspapers on the floor and sleeping on those, curled up like hamsters between the seats. A few who didn't have newspapers took down the curtains and slept on those. Despite the cramped conditions, there was a friendly and lively atmosphere on the train. An urn at one end of the carriage dispensed hot water with which people made cups of tea and pots of instant noodles (a 'cold meal' being a contradiction in terms to the Chinese).

At dawn we reached the small city of Pingyao. Over the past few decades, Pingyao has been something of a backwater, a city with little place in the heaving industrial machine that is modern China. In some ways this was the city's salvation, since it meant that the historic city centre, and the impressive walls surrounding it, were spared from the Communists' modernising bulldozers. Consequently, Pingyao is now one of the best places to soak up the ancient atmosphere of imperial China - narrow streets of one-storey buildings and courtyards, picturesquely constructed out of dark brick and hung with ornamental red lanterns.

The historic courtyard of the guesthouse at which we stayed in Pingyao

Unfortunately, other tourists had long since 'discovered' Pingyao, and whilst I don't mind sharing a place with other Westerners, I do mind sharing it with the pushy salespeople and pedicab drivers who follow them like flies. There seemed to be nowhere in China that foreigners could escape attention. In well-travelled areas we were badgered to buy things, whilst elsewhere we had to accept constant stares and shouts of "Hello!" or "Laowai!" (a Chinese equivalent of the word "gringo") from passers-by. Although we told ourselves that people were merely being friendly or curious, and didn't mean to come across as rude, the constant attention became very tiresome. The days in which China's state bureaucracy took it upon itself to make life uncomfortable for foreign visitors may be long gone, but a billion inquisitive citizens have taken over the task with enthusiasm.

Zhengzhou

From Pingyao, two more long train journeys took me to Zhengzhou. Though it is the most populous city in the most populous province of the most populous country in the world, Zhengzhou is an utterly unremarkable place - a nondescript modern settlement in which six million dull, ordinary people lead dull, ordinary lives. Among them was my flatmate Ben, who travelled to Zhengzhou from Shanghai and won his 'bet' by immediately finding a teaching job at an English-language college.

There is a massive unfulfilled demand for English teachers in China, and Ben - by virtue of being white and having English as his native tongue - was amply qualified. His job provided him with a good salary (once again, by virtue of his being white), and company accommodation: a small, modern bed-sit in a clean apartment block a few miles from the city centre. The place had a DVD player (DVDs of the latest Hollywood movies could be bought for the equivalent of less than a dollar from the local shop, no questions asked) and a television tuned to CCTV9, China's English-language news channel. The majority of the news items on CCTV9 highlighted China's economic progress and its friendly relations with other countries (including North Korea, which Chinese newsreaders referred to by its ludicrous official name, the Democratic People's Republic). I'm told that China's news is not as bad as it used to be, but a certain amount of obvious censorship remained, and not just on TV; the country's Internet cafes blocked access to inconveniently truthful web sites such as BBC News Online.

Ben and I visited the park in the centre of Zhengzhou, and went boating on a small lake where children washed themselves and filled drinking water bottles, seemingly oblivious to the lake's algal green colour and the dead goldfish floating on the surface. The park also included a grim aviary full of once-magnificent birds imprisoned in various states of unhappiness. The centrepiece of the aviary was a giant eagle, fixed permanently to a post where it sat miserably in the heat with it is wings hunched and its eyes rolling in despair. Beside it was a banner displaying the golden arches of a familiar fast food chain, and the slogan "I'm lovin' it".

That evening I went out with Ben and his Chinese colleagues for dinner, which consisted of small pieces of meat and vegetable that we boiled in a big pot at the centre of the table before fishing them out with chopsticks - a tricky procedure that left behind even more mess than the average Chinese meal. I thought I'd mastered the correct use of chopsticks by this point in the trip, and it was only after scalding my fingers a couple of times in the boiling liquid that I noticed that I was holding mine in a different way to that of my Chinese companions.

The journey home

Ben and I left Zhengzhou the next day, and flew back to Shanghai. (Ben had intended to stay and continue his teaching job for the rest of the summer, but inflexible airline tickets and the utter dreariness of Zhengzhou drove him home.) Shanghai seemed even more futuristic than it had two weeks before. On the side of one of the skyscrapers a panel of intense lights functioned as a gigantic TV screen, perhaps a hundred metres in diameter, beaming out colossal and mesmerising advertisements for the latest consumer goods to the citizens of the People's Republic.

Following the previous week's book launch, the Del Boy-like characters who sidle up to tourists and offer them dubious merchandise had added a new phrase to their limited English vocabulary. The furtive offers of "Watch? DVD? Sport shoes?" (or, on the dodgier streets, "Hash? Girls?") had now been joined by "Harry Potter?".

Having resisted the temptation to buy a fake Rolex, or a copy of the boy wizard's latest adventures, we returned home to Britain. On the way we experienced one final example of China's spectacular modernisation: the shiny new Maglev train that propelled passengers from its terminal near the centre of Shanghai to the city's Pudong airport at 270 miles per hour (430 km/h). The Maglev was more of a rollercoaster ride for rich businessmen (Ben's description) than a serious mode of transport, but it provided a thrilling end to our stay in China. We decided to burn some spare yuan by riding "VIP class" (the cost was still only half that of London's Heathrow Express), and ended up with an entire carriage of the train to ourselves.

"A rollercoaster for rich businessmen": the super-fast Maglev train at its terminal in Shanghai

Our flight to London departed from the thirteenth gate of Pudong airport, which the superstitious Chinese had designated as Gate 14. This didn't stop it being unlucky: our plane from Shanghai was late, as a result of which I missed my subsequent flight from London to Edinburgh, and found myself returning to Scotland on the overnight bus instead.

After spending the past couple of weeks being stared at as I fumbled with chopsticks, I took a certain pleasure in watching the Chinese passengers on the plane get to grips with their knives and forks. Many gave up and ate with their spoons. One produced a cocktail stick from somewhere and skewered his food with that, rather than attempting to use the fork. (I shouldn't have felt so smug - I seldom use a knife and fork in the correct way either.)

I wonder if those Chinese passengers found their visits to Britain as stressful and strange as my visit to China.

This account of my trip is adapted from the various emails that I sent home.

Disclaimer - this is just my personal experience, it isn't a travel guide. China is changing rapidly, and much of what I have said about the country may be out-of-date by the time you read this.

Unless you have visited every other country in the world and run out of places to see, I don't recommend that you go to China.