14 September 2006

While Ranwadi slumbered during the holidays, I heard that a big fundraising event was being organised at Bwatnapne. Nobody seemed sure what was being planned, but this being Pentecost, it seemed likely to involve dead bullocks, kava, and long 'talk-talks' by local dignitaries who had acquired their positions on the basis of their family connections or their willingness to slaughter pigs rather than their ability to give speeches. I decided to go along.

My intention was to complete the ten-mile walk to Bwatnapne in the morning, stay for an hour or two at the event, and turn around and walk back. Sara and her father, who were also going to Bwatnapne, suggested that I walk with them. They planned to leave Melsisi at 11 o'clock in the morning, as soon as Sara had finished a meeting with her teaching colleagues. Of course, Sara's meeting overran - meetings in Vanuatu always do - and it wasn't until after lunch that we set off over the hill to Bwatnapne. Conscious that it was getting late, I began to walk on ahead. By the time I arrived the afternoon sun was slanting low against the headlands at either end of Bwatnapne Bay. No problem, I thought: I'll have a quick look around, turn around and head home.

Unfortunately, I had arrived just in time for the speeches. In a clearing on the shore, a long succession of minor chiefs and government officials dressed in their finest Hawaiian shirts were taking turns to ramble into a microphone, while a gathering of villagers listened lazily. A large set of loudspeakers, turned up to a high enough volume to drown out the noise of the generator powering them, sent the speeches resonating across the bay. (Judging by the air freight stickers plastered on them, the loudspeakers had been brought in specially from town.) Slabs of dismembered bullock hung from the trees, and at the back of the crowd a group of men with bush knives hacked kava roots into tiny fragments, ready for grinding.

I stood at the back of the crowd, trying to look inconspicuous as I prepared to slip away. Being white, I failed.

"You come," a man whispered. I was led to the front of the audience and seated on a plastic chair, next to Ian the Peace Corps volunteer (the only other white person in attendance), and a garland of leaves was hung around my neck. Though nobody knew I was coming, I was being treated as a VIP guest. There was no way I could leave now.

"Don't worry," Ian whispered. "When the speeches are over, there'll be plenty of kava."

"That is a worry," I told him. "I need to be back at Ranwadi first thing tomorrow morning."

I sat back and listened to the speeches. One speaker was reading statistics from a recently-published booklet about Vanuatu's education and its economy. As a piece of public oratory it was appalling (twenty minutes into his speech, he apologised for being unable to talk in more depth on the grounds that he had been given a five minute time limit), but he made some interesting points.

Economically, Pentecost is doing well, it seems. Thanks to the high price of kava - Pentecost's main export - plenty of cash is flowing to the island. There is only one sensible way to invest that money, the speaker told his audience: in educating our children. Yet, when it comes to education, Pentecost ranks among the worst islands in Vanuatu. If I was interpreting the morass of statistics correctly, nearly a fifth of Pentecost's children don't even attend primary school.

"From kava, plenty money ee come 'long Pentecost," he told the villagers. "Me want'em ask'em: money here ee go where?" Where has all the money gone?

The portable DVD player that I could see through the doorway of a nearby hut hinted at the answer.

In between the speeches, I asked Ian what the event was all about. The aim, I discovered, was to raise money for a local fish marketing co-operative. (The scheme appeared to have got off to a good start: at the mouth of the river nearby was a newly-built bamboo hut, containing three or four big freezers that definitely smelled as if they were full of fish.) The fishermen liked the idea of a co-operative insofar as it helped them to sell their produce, but didn't like the suggestion that they ought to invest their own money in setting it up. Throwing a party seemed like a much better way of raising funds. I had to agree.

The final person to take the microphone was a singer who had flown in from Santo Island for the occasion. As the sun set and reggae music (the soundtrack of tropical islands everywhere) drifted across the beach, the party got underway. Parcels of food wrapped in giant leaves were bought and sold, a crowd of men gathered around a bucket of kava, a dancing ground was prepared, and a group of villagers debated which freezer in the fish hut to unplug in order to free up a socket for the DVD player. I wandered around chatting to people I knew (many of Ranwadi's students and teachers come from villages above Bwatnapne), and to people I didn't know who were keen to find out who I was and where I had come from.

"Name b'long me Andrew," I said to a group of children who were staring at me with particular curiosity. "Me b'long England."

The children stared blankly.

They don't speak Bislama yet, explained one of their mothers.

"Hak ah Andrew," I repeated. "Nana atsi at England."

My garbled pronunciation of their native language was unintelligible to the children, but entertained their mothers greatly.

"By-and-by you dance?" they asked.

I couldn't stay for the dancing, I explained: I had to leave. I needed to go to the airfield the next morning to collect mail, and the next afternoon I had arranged to give a tutorial to the Year 13s, who were still at school. (When the Year 13s subsequently failed to turn up to their tutorial, I was furious.)

I said my goodbyes, explaining to various horrified partygoers that, yes, I really was planning to walk back to Ranwadi in the dark. Pentecost is one of the safest places in the world to walk alone at night (for men, at least), but the locals don't see it that way. They inhabit an island populated by imaginary ghosts and devils.

My main torch was out of batteries, and clouds had covered the moon, but I had one of my miniature keyring lights in my pocket (I always do), and the little LED illuminated the ten-mile trek home. I began to appreciate why the locals value the tiny torches so much.

Soon after I began the uphill trek out of Bwatnapne, it began to rain. It wasn't a pleasant walk home.

I returned to Ranwadi, exhausted and soaked, just before midnight, and found the house strewn with baggage and sleeping Australian girls.

Five gap volunteers from Ambae Island had come over to Pentecost for the holidays, and since there was little room for guests at Dani and Nat's annex beside the girls' dormitories, I had left them the keys to ours. Three of the gappers were sleeping in Hugh's empty room (he had gone away for the holidays), while the other two crashed in the dining room, amongst my piles of half-mended Maths textbooks.

The next day, the crowd of teenagers hiked up the mountain to a waterfall high up the river, startling a local chief in his garden. The chief hid in the bushes until they had gone (he told me afterwards with a smile), frightened to talk to them.

(The chief was not the only person hiding on the mountainside that day. A policeman had come to Pentecost to arrest the arsonist who had run away from his trial at Melsisi a couple of months earlier. The fugitive was tracked down in a house in the jungle, and apprehended. The policeman hadn't brought any handcuffs, but the dangling roots of a nearby banyan tree were cut and used to bind the prisoner's hands. He was led down the hill and onto a ship, bound for Luganville prison.)

Unsure whether or not I liked having the house invaded by teenage girls, I spent the evening down at the nakamal, where the villagers sat and chatted about refreshingly male topics. First there was talk about electronics. A man's uncle had recently bought a solar panel for his house and wanted to know if I could find out the price of an inverter to plug into it. I said I'd look on the web at the start of next term (Internet access isn't available at the school during the holidays).

The conversation then moved on to football. Somebody had heard that a court had ordered the World Cup final to be replayed; we suspected that this was "coconut news", but with no regular news media (and currently no Internet access) on Pentecost there was no way of disproving it. We debated for a while whether or not a court had the power to order a World Cup replay.

Another news story that was discussed at the nakamal concerned HIV. A new case of the illness had recently been announced in Vanuatu, bringing the country's total number of HIV sufferers to three (although health workers suspect that several more remain undiagnosed). HIV is a new problem in Vanuatu - the first official case was only four years ago - and the potential for the virus's spread is causing considerable alarm. At the nakamal there was a long and uninformed discussion about the disease, accompanied by some unnecessary and slightly offensive advice about how I should take precautions if I was ever tempted to use prostitutes when passing through Port Vila.

Talking of girls, the villagers wanted to know, where on earth did all those "white misses" come from? Were they sleeping in my house? Were any of them sleeping in my bed? And (from the younger men at the nakamal) if not, why not?

I explained that the Australian girls were merely taking advantage of spare beds and floor space. Guys and girls sometimes share houses in countries like ours, I said; it doesn't mean that they're sleeping together.

"You should take'm one with'em glass," one of the men suggested. (When I later found out which of the gappers had been wearing sunglasses that afternoon, I was interested to note that despite our cultural differences, the villager and I had come to the same conclusion about which girl was the most attractive.)

As if to complete the evening of masculine conversation, the topic of burping and farting arose. (I'm not sure how.) The villagers asked me about Western attitudes to these bodily functions, and explained their own customs. Farting is OK amongst friends, they reassured me. However, doing it in front of one's father-in-law is a serious transgression, for which the "polluter" must pay a pig in compensation.

After three months on Pentecost, I decided that it was about time I bought a 'bush knife' - one of the long machetes that the islanders carry and use for just about everything from slicing fruit to mowing lawns. I wasn't exactly precisely what I would use it for - I have kitchen knives to slice fruit and students to mow the lawns - but I was sure that it would come in handy sooner or later.

Sadly, a use for the knife turned up the next day, in the form of a stray cat that hauled itself weakly onto our doorstep. The helpless creature was badly injured (probably the result of a stone thrown by some bored child) and clearly in pain.

There are no vets on Pentecost.

I slept badly that night, haunted by sounds and visions of invading rats, scurrying cockroaches, marauding hounds and dead cats. The next morning, I was unsure of how many of these animals had been real, and how many I had dreamt.

I was fairly sure, for example, that my encounter with a giant rat in the bathroom at one o'clock in the morning had actually happened. The scratch of its sharp little feet against my skin as it used my hand as a stepping stone to jump down from the door frame to the floor, and the silhouette of the desperate rodent scuttling round and round the tiny room in search of a bolthole while I tried unsuccessfully to corner the creature and cast around for something to whack it with... these were too vivid to have been dreamt.

The hounds, too, did exist - I woke the next morning to find our dustbin overturned and muddy paw prints around it - but in reality I had merely heard them outside my window. In my dream they were visible and slavering.

I piled rocks around the bin to keep the dogs from overturning it again, and indoors I set a rat trap, baited with peanut butter. (Rats, like Americans, are extremely fond of peanut butter.) The rat in the bathroom was not the first that I had noticed in the house; I had been wrong to think that the cracks in the walls were too small to let them in. When I first moved in, the house's main pest problem had been cockroaches, but my extermination of the roaches appeared to have opened up an ecological niche. Just like in the aftermath of the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs, small furry mammals were soon poking their heads out of crevices and taking advantage of the opportunities now available to them.

On the fifth anniversary of my first arrival in Vanuatu, I spent the day doing a very Vanuatuan thing: waiting. The gap girls from Ambae wanted to return to their island, and since there was still a week of the holidays left, the two Ranwadi gap girls and I decided to go with them. As usual, the little planes that hop between the islands were fully booked, but we heard that a cargo ship bound for Ambae was coming past on Saturday. Maybe. Shipping schedules in Vanuatu are frustratingly vague. When Saturday came, there was no sign of the ship, and when we tried to phone the shipping company to ask about its progress, we found their office closed for the weekend.

For nearly forty-eight hours, the eight of us took it in turns to look out for the ship. Meanwhile we read books, and watched the magical adventures of Harry Potter - one of the most fabulous pieces of escapism ever invented - on my laptop. We invited our next door neighbours and their children to come and watch the DVD with us, and I did my best to translate the dialogue into Bislama. (I wonder if they spotted the many parallels between Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and their own institution: the fear of black magic; the unquestioned existence of ghosts and demons; the abundance of rats, bats, and spiders; the way the school is answerable to "the Ministry"; the relative isolation from the modern world; the frequent use of old-fashioned artefacts like candles in place of electrical technologies; the relative disregard for safety; the occasional use of curses to punish misbehaving students; and the psychological gulf between magically-minded locals and 'Muggles' such as myself.)

Late on Monday morning, the ship finally appeared. We rushed down to the landing spot - a point on the beach where there is a slight gap in the reef - and piled up dead palm fronds and coconut husks into a flammable heap. Like the lost boys in Lord of the Flies, people in Vanuatu light fires as a way of attracting a ship's attention: during the day the smoke is visible for miles, and at night it's hard to miss a glowing fire on an otherwise utterly black shoreline.

The ship - the M.V. Halice ('H' is often silent in Bislama) - idled in the water, safely beyond the reef, while the crew sent ashore a small motorboat to pick us up. We clambered on board and settled down for a long trip.

By the standards of Vanuatu's inter-island vessels, the Halice was a reasonable boat. In addition to a cargo area stacked with boxes and petrol drums, there was a small passenger deck where a few sleepy looking islanders slumped on wooden benches, or hunched on pandanus mats on the rusty floor. Many had been on the ship for days, yet few were reading books, or playing games, or listening to music, or watching the scenery. Most didn't even chat very much. They simply sat, showing off the Melanesians' most remarkable talent: their contented ability to do absolutely nothing.

As a Westerner tormented by time, I seldom travel anywhere in Vanuatu without a book. Carrying reading material to protect myself against the local languor is almost as essential as carrying sunscreen to protect myself against burning, or carrying insect repellent to protect myself against malarial mosquitoes. On this occasion I amused myself with the story of Paul Theroux's travels in this part of the world, The Happy Isles of Oceania.

"The Australian Book of Etiquette is a very slim volume," Theroux wrote, "but its outrageous Book of Rudeness is a hefty tome. Being offensive in a matey way gets people's attention, and Down Under you often make friends by being intensely rude in the right tone of voice."

I tested the theory by reading this passage, and various similar ones, out loud to my Australian companions. Their reaction wasn't friendly. Clearly I was using the wrong tone of voice.

For the rest of the day, the Halice chugged northwards along the coast, its crew keeping a lookout for fires on the beach and stopping every couple of miles to send a boat ashore for cargo or passengers. Flying fish jumped out of the way, flitting and twitching their fins as they skimmed the water. A fishing line was trailed from the back of the ship, and at one point an impressive marlin was hauled aboard. The marlin disappeared into the galley, and emerged at dinnertime in the form of juicy slabs atop plates of greasy rice.

Meanwhile, the coast of Pentecost rolled past like a tapestry - familiar villages and landmarks painted from an unfamiliar perspective. From the water, it looked quite unlike a tropical island. The dark, forested mountainsides, with inky water reflecting the grey sky, resembled the walls of a Scottish loch or a Norwegian fjord. The palm trees lining the shoreline and dotting the jungle seemed incongruous and ugly in such surroundings. It is not surprising that Captain Cook, who must have had a similar view of Pentecost from the deck of his ship, named Vanuatu the New Hebrides, after the bleak Scottish archipelago.

A lot of Melanesian islands look like this, yet somehow people do not expect the South Pacific to be mountainous: the tourist-brochure image is of thin, sandy atolls. Friends from home who've never heard of Vanuatu occasionally ask if it's "the place that's going to disappear because of global warming". In truth, Vanuatu is probably in less danger from global warming than any other coastal country. Not only is much of its land area high above the ocean, but (unlike in most countries) its population and agriculture are not concentrated in floodable lowland cities and farms. Migrating up the mountains to escape rising sea levels will cause a lot less hassle to the villagers of Vanuatu (who have to rebuild their wooden huts every few years anyway as cyclones and decay take their toll) than it will to the citizens of London and New York.

Just after nightfall, the Halice reached Laone, at the northern tip of Pentecost. Here it took on board sixty Anglican women who were on their way to a church conference on Ambae. The women sang choruses of "Jesus ee number-one" and other favourite 'sing-sings' as the ship left the sheltered coastline and struck out into the rolling strait between the islands. Outside, the water was black and menacing; the land beyond was blacker still. Looking out over the deck, the ship suddenly seemed small, and the Pacific Ocean gigantic beyond comparison. The waves swelled and subsided, not ferociously, but strongly enough to remind me that I had put myself at their mercy. As the churchwomen chanted their hymns, I felt as if I was on a boat of departed souls saying their last prayers as they crossed the river into the Underworld.

It was after midnight when the Halice reached Lolowai, at the eastern tip of Ambae. There the ship anchored for the night.

"Do you want to go ashore now, or in the morning?" the Captain asked. The grimy deck of the ship wasn't a comfortable place to sleep, but the shoreline outside was black and unknown, and I didn't fancy trying to find accommodation at such a late hour. We chose to stay on board.

I was woken in the usual Vanuatu way - at dawn, by the crowing of roosters (were there roosters on the ship?!) - and got my first close-up look at Ambae.

The Halice in Lolowai Bay

From Pentecost, I had seen Ambae many times in the distance; it looked smooth and blue and inviting. I was not the only one who had once gazed dreamily at the island's misty silhouette. The writer and serviceman James Michener also had a distant view of Ambae from his World War II base on neighbouring Santo; he dreamed of sailing to that mysterious island, falling into the arms of a beautiful woman and finding an escape from the misery of wartime. Thus the legend of Bali Ha'i was born.

I don't know how James Michener, who never actually visited Ambae, pictured his fantasy island. However, the images of Bali Ha'i in the minds of those who read his Tales of the South Pacific are probably quite different from the reality of the place that inspired it.

Ambae is certainly beautiful, but not in a paradisial way: you will find no golden sands or turquoise lagoons there. The island is volcanic, and has the dark, primeval look of a freshly-erupted landscape. The rocks on the shoreline are black lava, with the appearance of barely-congealed treacle, and its beaches are like powdered asphalt. The surrounding sea, reflecting the island's blackness, is the colour of children's paint that has been too thickly mixed. Lolowai harbour is a sunken crater, surrounded by dark cliffs.

At Lolowai the gappers teaching on Ambae, whose school is further along the island, remained on the ship, while Dani, Nat and I got into the little motorboat to be ferried ashore. (Down on the cargo deck, I noticed crates of livestock amongst the boxes and petrol drums. There were indeed roosters on board the ship.)

We landed at a beach the colour of pencil lead, where disgruntled brown pigs sat in crudely-constructed cages awaiting shipment to Port Vila. Uncertain of where to go (there are never any signposts in rural Vanuatu), we trudged up to what seemed like the centre of the village, along what seemed like the main road.

"Hello, Mr Andrew," said one of the passers-by. Many of Ranwadi's students come from Ambae.

It's bizarre that I can spend a day and a night on a ship, land at a mysterious South Pacific island that I've never visited before, and encounter people who know me.

Lolowai is a well-developed village, with a bank, a post office, a small hospital and a sleepy commercial centre, all housed in sturdy concrete buildings. Many had clearly been built with foreign aid money; a plaque on one building proclaimed friendship between the Republic of Vanuatu and the people of Japan. (I wondered which of Vanuatu's natural resources the Japanese wanted in exchange for their friendship.)

The concrete amenities were not the only signs of modernity. On a nearby hill, I noticed a mobile phone mast (probably newly installed as part of the American-funded programme to bring mobile networks to Vanuatu's islands), and down in the village a crude laser-printed sign on one concrete doorway announced the existence of "Lolowai Internet Café". The café's two computers weren't actually connected to the Internet access yet - Telecom Vanuatu promised to hook up the phone line "tomorrow" - but the owner was hopeful about his new venture.

We sat outside, watching volcanic dust billowing along the road (the stuff wrecks his computers, the owner complained), and chatted about the opportunities that the Internet access could offer to people in rural Vanuatu. Unfortunately, at the prices the Lolowai Internet Café would be forced to charge in order to recoup its costs, it seemed unlikely that many locals would be able to take advantage of it. The owner expected his main customers to be the yachties who frequently anchor in Lolowai's natural harbour. Public Internet access seemed destined to be the latest in a long list of foreign technologies introduced to Vanuatu primarily for the benefit of foreigners.

It was a shame that the Internet café hadn't opened a week earlier, when people from all over Vanuatu (including most of the country's dignitaries) had come to Ambae for the Provincial Games, a national sports extravaganza. Back down on the beach we met Mr Noel, who had come to Ambae to help with the scorekeeping at the tournament, and was now waiting (alongside the pigs) for a ship to take him to Vila.

Accompanied by Noel (who didn't expect the ship until late in the afternoon), we walked to the sports stadium, which was a couple of miles away, along a badly-eroded dirt road that clung precariously to the rim of an ancient crater. The roadsides were as thickly forested as anywhere else in Vanuatu, yet remarkably, the trees and vines appeared to be growing out of pure, brownish-grey dust. It was as if somebody had planted a jungle on the moon. The road was choked with this filthy dust, which stuck to sweat and sunscreen to form a grimy layer on our feet and legs.

From Vureas we left Mr Noel and set off inland. Our aim was to see Ambae's famous crater lakes, which sit atop the island inside in an enormous volcanic caldera several miles wide and nearly a mile above sea level (making the lakes the highest in Oceania). We travelled uphill in the back of a pick-up truck, and then continued up the road on foot. (The truck's suspension was damaged, the driver told us, and it couldn't cope with the roads.) Up on the mountain, where conditions are wetter than on the coast, the dust had coagulated into thick mud.

For a couple of miles, we passed through homely, rural scenery - village gardens and meadows of cattle - interspersed with patches of tangled forest. In places, spectacular banyan trees draped with mosses and ferns arched over the road. As we ascended, the scenery became wilder, and the road (which had only been a dirt track to begin with) deteriorated into a slimy footpath. Eventually we reached the settlement of Duviara, the last outpost of civilisation on the mountainside. Beyond it lay a dripping green wilderness, and beyond that, the volcano.

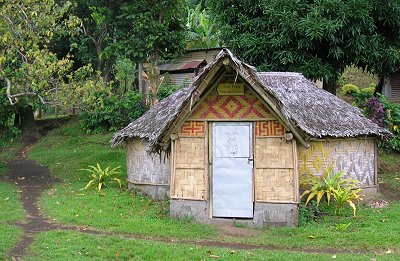

Duviara is the home of the energetic Paul Vuhu - schoolteacher, tour operator, churchman, gardener, cultural fieldworker, and football fan - and his extended family. Their little hamlet comprises a family home, a big thatched hut that serves as a kitchen and a nakamal, a tin-roofed chapel that doubles as a schoolhouse and library, various shacks in the bushes that function as bathrooms or toilets, and a bamboo-walled guesthouse. This is the Last Stop Bungalows: the last place at which travellers can stop and rest on their way up the mountain.

Paul greeted us enthusiastically at the door of the chapel, as if he'd been expecting our arrival. (In fact we'd failed to let him know that we were coming, but since his guesthouse is miles from the nearest telephone, Paul must be accustomed to unexpected visitors.) He was especially welcoming when he had discovered where we had come from. Paul knew Ranwadi well: he had worked there himself as a trainee teacher, and his two eldest sons attend the school (one is in my Year 7 Science class).

In the thatched hut, Paul and I shared stories over a couple of shells of home-grown kava (a distinctive Ambae variety with a faintly peppery taste), while his family prepared dinner. The two gappers, still fairly new to Vanuatu, listened to the Bislama and watched the cooking with interest. Pieces of taro (the starchy local root vegetable) were grated into a paste and wrapped in banana-like leaves. The package was tied up using twine made from the midribs of the leaves and then baked in a fire under hot stones to make a chewy slab of laplap, which was topped with freshly-made coconut cream. The fire filled the hut with smoke, which made our eyes stream, but the warmth was welcome - nights on the mountainside are surprisingly cold. One of the boys killed and plucked a chicken, which was also cooked on the fire, while another went fishing for prawns in the local streams. After the delicious meal, we said "bon karea" (goodnight, in the local language) to Paul and his family, and retired to sleep in the bamboo guesthouse.

We woke early the next morning, and were met outside by Simeon, the local man who would be our guide on the trek to the top of the volcano. For three hours we picked our way along a slippery footpath that climbed through misty cloud forests, where everything we touched was green, absorbent and dripping with moisture. It was the kind of forest in which you would expect to find David Attenborough whispering to a camera while peering through the fronds at a family of gorillas or an unusual species of parrot, or maybe a computer-generated dinosaur. I was disappointed to learn that this forest was, in fact, almost devoid of animal life - not even wild pigs lived up here. The treetops were damp and silent; even birds and insects were scarce.

As we neared the crater rim, the forest began to lose its lushness, and the dripping boughs gave way to thin, sickly-looking tree trunks. Many of the leaves were brown and dead, and the place had the general appearance of a landscape poisoned by pollution. This pollution was not man-made - we were thousands of miles from cities or factories - but came from the gases belched by the volcano. The acrid, eggy stench of sulphur drifted down through the trees.

Much of the damage to the forest had probably occurred at the end of last year, when Ambae's volcano erupted dramatically, making news stories around the world and prompting the government to order the evacuation of large parts of the island. I asked Simeon what had happened to his village at the time of the eruption.

"Time way volcano ee fire-up big-one, you-fella ee go 'long some 'nother place?" I asked.

He shook his head. "Me-fella ee no go."

Although Simeon's village was one of the closest to the volcano, the people there had opted to stay behind while the rest of the area was evacuated. They knew the volcano better than anyone, and realised that their village was not in danger of destruction. It was a good thing that they stayed, Simeon told me, since the villagers' local knowledge proved valuable to the scientists who came to monitor the eruption.

"Volcano ee no chuck'em shit 'long all garden b'long you-fella?" I asked.

(Bislama evolved from 19th-century sailor talk, and some of its vocabulary reflects this. "Shit" - or "sit" as it's normally rendered - is a legitimate word meaning ash or detritus, not to be confused with "shit-shit", which is the genuine article.)

"Oh, him ee chuck'em," Simeon said. "But him ee no spoil'em garden." In fact, small doses of volcanic ash actually help to nourish Vanuatu's soils, and partly account for the islands' spectacular fertility.

However, there is only so much volcanic shit that a forest can take. When we reached the crater rim and saw down into the caldera, the trees looked tormented and brown. In the distance, plumes of steam marked the position of the lakes.

Do not speak badly of this place while we are walking, Simeon warned us, as we scrambled down muddy slopes into the caldera. We do not want to offend the spirits who live there.

For another hour we trailed through the haunted landscape of the crater's interior. It was a tortuous journey: clambering up banks and sliding down gullies, ducking over and under the stems and branches of fallen trees, tripping on rocks and roots, and squelching through poisonous-looking mud. It was a relief when we ascended a final slope and reached the rim of Lake Vui, the lake in the centre of the caldera.

It was a deeply unnatural sight. The lake was far below us, at the base of steep cliffs rimmed by the white skeletons of long-dead trees. In the centre of the lake was a mound of ash, tinged with yellow sulphur, with a vent on top from which white steam billowed high into the air. The mound was an island within an island, a volcano within a volcano. The lake itself was crimson red, especially at its margins, where the water was like blood. This redness is a new phenomenon, I was told - one that has only emerged since last year's eruption.

I ought to have been awe-inspired, yet somehow I wasn't. Perhaps I was simply jaded by experience: I've seen crimson lakes and smoking volcanoes before. However, there are many other sights in Vanuatu that continue to amaze and impress me - waterfalls on Pentecost, for example - even though they are hardly new. The main problem with Lake Vui was that it just didn't look like a natural phenomenon - it looked like a polluted pit. The scene reminded me of quarries and mines, viewed from the windows of English railway trains, or of pictures in posters put up by environmentalists warning society not to create sights like this. I have become so accustomed to regarding smoking heaps, dead trees and discoloured water as ugly and undesirable that I was unable to appreciate that they occasionally form a legitimate part of Nature's beauty.

The crater lake on Ambae. In real life it's red.

Having travelled for days to get there, I could not even take away an accurate picture of the place. The lake's amazing crimson colour, Simeon told me, does not show up properly in photographs. Sure enough, when I looked at most of my pictures only a hint of redness could be seen. Instead, the water shone blue - the reflected blue of the sky. The human eye (or rather, the human brain) compensates for such reflections far better than a camera can. My mental image of the place was the only accurate picture I had, and by looking at the photographs I have probably corrupted even that image, leaving me uncertain about how red the lake really was. Unless I return, I will never know.

The next day we got a truck down the mountain, and then hiked westwards in the direction of Londua School, where the other gap volunteers were based. After three or four hours - a long, hot, dry walk - we reached the village of Nangire. Beyond Nangire, the road came to end, and we hired a speedboat to take us the rest of the way to Londua. The gap in Ambae's northern coastal road isolates the villages of north-eastern Ambae from those in the north-west: people talk about East Ambae and West Ambae as though they are separate islands. When I first saw a map of Ambae, this gap in the road seemed bizarre, but after seeing the terrain it no longer surprised me. Looking at the coastline from the speedboat we could see perilous cliffs of volcanic rock, convoluted like curtains, falling steeply into the sea. Only the Scandinavians would attempt to build a road in such a place. For the people of Vanuatu, with far less money and dynamite at their disposal, sailing around the cliffs in canoes and speedboats made far more sense.

At Londua, we clambered out of the speedboat onto black rocks that looked as if they had cooled only yesterday from molten lava. As we made our way up to the school, in search of the gap girls, we saw a stocky, smiling figure walking towards us under the coconut trees. His dark, round face had an oddly familiar appearance.

"Welcome to Londua, Andrew."

Londua School is run by Graham Bule, whose elder brother Silas is the Principal at Ranwadi.

Both Principals are relaxed, friendly and thoroughly helpful men. However, in other respects they are notoriously different characters. Silas upholds the values of the Churches of Christ by refusing to touch alcohol or kava, or allow them to into his school. Graham upholds those values by stopping in a nearby coconut plantation to finish off the tins of rum cola that he buys on his way home from the kava bar, so that he does not have to bring them into the school. His approach made a refreshing change from the uptight (and, according to some Churches of Christ members, scripturally misguided) attitude towards kava-drinking that is taken by many of my Ranwadi colleagues.

That night, I accompanied Graham to the kava bar, together with some of the gap girls and Graham's daughters, one of whom is in my science class at Ranwadi. (I felt awkward drinking kava in front of one of my students, for a second time that week - the sight of teachers getting stoned on narcotics struck me as the kind of thing that would normally result in letters to the school from furious parents. However, since on both occasions the drug had been offered to me by the father of the students involved, I didn't think that such complaints were likely!)

The atmosphere of West Ambae was quite different from that of the east. The shoreline is cut from the same black volcanic rocks, and the roads are coated with the same filthy dust, but in other respects the west of the island is far gentler in its scenery. Flat roads wind amongst groves of coconuts and cocoa, and alongside the traditional thatched huts there are well-built, suburban-looking houses and stores. The signs of Westernisation are slight and superficial - most of the villagers still live primarily from their gardens and follow their traditional habits - yet on Ambae there is a forward-looking sense of modernity that Pentecost somehow lacks. The people of Ambae are equally as friendly as those on Pentecost, and in many cases seem more comfortable and open in the presence of visitors. On Ambae, old women on the road do not avoid eye contact with foreigners for fear that they will be spoken to in a language they don't understand, and young children do not react to the sight of white people as though confronted by ghosts.

Dani, Nat and I passed the rest of the week with the gappers at Londua, waiting for a ship back to Pentecost. (When typing the first draft of the last sentence, I ended it unthinkingly with the word 'home'.)

Life at Londua was a lethargic mixture of reading, writing, cooking, walking to neighbouring villages, swimming in the sea and (for some of the gappers) 'sunbaking' from 12 until 2 every afternoon on the scorching black rocks below the school. The sunbaking astounded me: Australians are taught from a young age about the dangers of overexposure to the sun, and are well aware that it not only puts them at risk of life-threatening cancers but will leave their skin wrinkled and unhealthy in later life. In the spirit of friendly Australian rudeness, I pointed out to the girls how stupid their daily activity was. They merely shrugged, and explained that they couldn't possibly return home without a thorough tan.

When a ship came past, bound for Luganville, Dani and Nat jumped on board. They spent the last couple of days of the holidays in town, eating hot pizzas and drinking cold smoothies. I preferred the quietness of Ambae, and opted to remain behind and wait for a ship going directly back to Pentecost. I made myself useful to the Ambae girls by showing them how to bake chocolate cakes on an open fire (their house had no oven), and in return they put up with my periodic ranting about the inexplicable and seemingly-idiotic habits of Australian teenage girls.

On Sunday night, I hear rumours that a Pentecost-bound ship was expected the next morning. Uncertain what time it would arrive, I got up at 1 a.m. and spent the rest of the night snoozing on the shore below the school. It was a clear night and the rocks were drenched in moonlight. I found a flat spot by the shore and rested there on a head of dry palm leaves, listening to the sucking of the tide around the rocks, and watching the flying foxes and the shooting stars.

Just before dawn, I saw the lights of the Halice in the distance. I jumped up and set my makeshift bed on fire to attract the ship's attention. I needn't have hurried. The indented coastline concealed some large villages, and the ship idled at these for three or four hours, loading and unloading cargo, before arriving at Londua. When the Halice eventually approached, I hauled some more coconut fronds down to the rocks to make a second fire, and the ship sent ashore a motorboat to pick me up.

Thirty hours and two thick books later, I was put ashore at Ranwadi, along with about twenty students returning from Ambae. (The motorboat was so perilously overloaded with students and their luggage that I seriously contemplated jumping out and swimming ashore.)

Officially, term had begun the day before, but I knew there was no danger that I had missed any classes. Many of Ranwadi's students and teachers were still on other islands. Even those who had booked flights to Pentecost in time for the start of term had failed to return, since once of Air Vanuatu's little aircraft was out of action and several flights had been cancelled.

The students and teachers who lived locally, meanwhile, were at Melsisi to watch a week-long sports tournament that culminated on 'Penama Day', a provincial holiday. Many had no intention of returning to school until the tournament was over.

Noel and Neil, having no classes to teach, had come down to the beach to meet the boat.

"We had a staff meeting yesterday," Noel told me. "Only five teachers were here."

I had plenty of time to recover from my trip before classes resumed.

22 September

Down at Vanwoki, a major event was taking place: the villagers were 'cooking mats'. Producing the long, red-patterned mats that are exchanged during ceremonies is a long and intensive process (which is presumably why the mats are valued so highly). I went down to the village during the school lunch break to watch.

I found the villagers gathered in small groups under the big mango trees in the centre of the village. A large number of people were there: not just the Vanwokians, but men and women from villages further up the mountain who had come down to take part in the mat-making. Fires were burning, and smoky sunbeams shimmered through the trees. In typical Vanuatu fashion, it was the women who seemed to be doing most of the work; the men sat in sleepy groups and watched. The village chiefs stood around supervising the proceedings and hobnobbing with neighbouring chiefs who had come along for the event.

Plain, brown mats had already been woven from strips of pandanus palm leaves, and were lying in heaps waiting to be dyed. Some of the villagers were cutting banana stems into the patterns with which the mats would be imprinted. Others were wrapping the mats tightly around the patterned stems before 'cooking' them in a long metal trough full of boiling red liquid, a dye made from water and ground-up roots. One or two people were tending the fires underneath the trough that kept the dye boiling. Two young women were extracting the newly-coloured mats from the trough and spreading them out to dry. Later, the mats would be taken down to the river to rinse off the excess dye, and the manufacturing would be complete.

These ceremonial mats are used as a form of currency, so what the villagers were doing was essentially printing money. I wondered if excessive mat-making ever caused inflation.

Cooking mats at Vanwoki

"'Long 'time before way all papa b'long you-fella ee got metal tank, all-ee cook'em mat all-same wanem?" I asked one of the villagers. How did your ancestors manage before metal troughs came along?

"All-ee cook'em inside 'long skin b'long tree," he told me.

"Him ee no burn?" Wouldn't a trough made of bark burn when fires were lit underneath?

"Fire ee no touch'em him." They kept the fires at a safe distance from the trough, and relied on the heat radiating from them to boil the liquid inside.

Cooking mats the old-fashioned way was slow and laborious, however. Containers made of bark were too small to take an entire mat; the dyeing had to be done in sections. The new metal tank, by contrast, was not only long enough for an entire mat but could take six at a time. Even the most traditional of practices, it seemed, were open to industrialisation.

The fires were still smouldering under the metal trough that evening, as Hugh and I walked through the dark village to the nakamal, where the men had gathered to drink kava and discuss the day's mat-making. The fires were not the only source of light, however. In the undergrowth by the path I noticed a bizarre green glow, and bent down to investigate. The ghoulish light was coming from a small mushroom growing out of a piece of rotting wood.

I picked up the piece of wood and took it to the nakamal, staring at the amazing luminous mushroom with much the same expression of wonderment that the locals adopt when they see my tiny LED torches for the first time.

The villagers nodded impassively. Yes, we get glowing mushrooms sometimes. You can find much bigger ones deep in the bush.

"Him ee make'm light from wanem?" I asked. Why does it glow? (I wasn't expecting a scientific explanation, but hoped for a good story.) The villagers had no answer. It was just an accepted part of their natural world: birds sang, flowers bloomed, insects buzzed, and mushrooms occasionally glowed green in the dark.

It seemed strange that people who often attach supernatural stories to the most mundane of things could find something as magical as a luminous mushroom so unremarkable.

30 September

After I offered my help to GAP Activity Projects in Vanuatu, they had a job for me: to visit the two Australian gap girls who had been posted to Paama Island, and report on their placement.

Happily, there are no direct flights between Pentecost and Paama. In order to get there, I had to spend a night in Port Vila, Vanuatu's capital, which gave me my only opportunity in six months for a cold milkshake, a proper hot shower, or a visit to a real supermarket.

My colleagues on Pentecost were only mildly interested in the fact that I was going to Paama, but when I mentioned that I was flying via Vila, their ears pricked up. The school bursar wondered if I could pick up a pile of stamps and phone cards for the school. The Principal wanted me to deliver money to his son at Malapoa College (a good excuse for me to have a look around what is officially the best school in the country - and marvel at the place's dilapidation). Hugh gave me his bank card and PIN and asked me to bring him back as much cash as I felt comfortable carrying. Several people gave me letters to post. Noel and Neil wanted me to buy rat traps (Neil had picked up four on his last trip to Vila, but decided that another ten would be needed to bring the school's rodent population under control). Nat wanted oats. Kate wanted liquorice bullets (whatever those were) - or, failing that, dark chocolate. The gap girls on Paama wanted me to go looking for a parcel of school supplies that had been sent from Australia but only made it as far as Vila. My biology class needed seeds.

I flew into Port Vila and found the town sitting in a hot haze. Taxis and minibuses bopped around the streets to the beat of funky music, while the sound system in the cool, shiny lobby of the Wild Pig Hotel serenaded visitors with its usual wonderful mix of classic soft rock tunes. When I arrived it was playing All Out Of Love, by Air Supply.

(Disappointingly, the sign outside the Wild Pig Hotel had recently been changed to "Coconut Palms Resort", a name so unmemorable I had to write it down. In protest at the name change I'll continue to refer to the place as the Wild Pig.)

A cruise ship had docked in Port Vila that day, and the town centre was full of bronzed, waxy-looking Australians, sweating into their fashionable clothes and wearing hats and sunglasses at the angle at which they looked coolest rather than the angle at which they best kept off the sun.

"Hey mate, does this thing spit out Aussie dollars?" asked the man standing beside me in the queue for the cash machine.

"Does it look like we're in Australia?" I felt like replying, but then looked around. Tanned white faces, sunglasses on foreheads, milkshake cartons in hands, silly souvenirs in the shop windows. It did look like we were in Australia.

"Nah, sorry mate," I told him. He walked off.

I spent the afternoon racing around town - with a look of such haste and purposefulness that nobody could possibly mistake me for an Australian tourist - and accomplished (or at least attempted) all of the errands I'd been given. I also visited the airline office and the immigration office, extending my stay in Vanuatu from November to December. (Teaching at Ranwadi will probably have ground to a halt by the end of November, but I'm in no hurry to leave.)

My final stop was the Au Bon Marché supermarket in the plush suburb of Nambatu. The Au Bon Marché is an expatriate lifeline: the only place in the whole of Vanuatu where Westerners can go and shop in the way they are accustomed to back home, pushing trolleys up shiny aisles where every conceivable kind of household item is stacked in convenient abundance.

I walked systematically up and down each aisle in turn, scanning the tens of thousands of products, nearly all of them unobtainable on Pentecost. (As a safeguard against buying more than I could carry, I wasn't pushing a trolley.)

Which would be the most useful things with which to fill the limited space in my luggage?

Tinned mushrooms? Too big and heavy. Dried mushrooms? Much better. I wondered if the mushrooms would spoil if I punctured the packets and let out the air so they would pack down smaller. Honey? Not unless I could find it in a plastic tub - I didn't want to lug a heavy, breakable jar around. Parmesan cheese? Great, if I could find the kind that doesn't need refrigerating. (I went and found it.) Whisky? No point - you don't need alcohol to enjoy yourself on a Pacific island. Baileys cream liqueur? No, really, you don't need alcohol. Real fruit juice? Much too heavy - the sickly synthetic fruit cordial sold on Pentecost would have to suffice. A tea pot? That would probably break. A tea strainer? Much less fragile. Dried raspberries? Mmm... dried raspberries. Too expensive, sadly. Instant oatmeal? There's a storekeeper on Pentecost who could supply us with that, but not in such a range of flavours. Jelly? I wondered if that would set without a fridge. Probably, if I used less water than the packet recommended. Ditto the instant puddings. A box of chocolates? Those would melt in the heat. (I bought them anyway.) Sticky rat traps? I didn't fancy wrenching off sticky rats. Cockroach poison? No, the house had been doused with enough insecticide already. Vanilla essence? That had better not leak in my bag. Liquid rooting hormone? Could be useful in science classes, or for the garden. I'd need to make sure that didn't leak either. Miniature fireworks? Surely Air Vanuatu wouldn't let me carry those on the plane. (They did let me.) Balloons? The Year 7s love those. Danish pastries? I bet the girls on Paama would appreciate them. Giant paraffin torches for the garden? If only I had the space in my luggage...

I made two or three trips back to the Wild Pig, my arms straining with plastic bags, and spent an hour or two compressing all of the shopping into my giant rucksack. Two or three plastic bags full of excess packaging were discarded in the process.

At the end of the day, the cruise passengers drifted back to their ship, like goggle-eyed aliens preparing to return to their home planet. Souvenir sellers packed up their stalls, tour operators stacked away their billboards, and Port Vila became once again a chilled-out Melanesian town. I stood on the waterfront and watched the cruise ship sail away into the sunset. The huge, blazing boat - its size and brightness dwarfing the dimly-lit, low-rise buildings of Vila harbour - really did resemble a departing UFO. Locals and expatriates, glad that the alien invasion was over, returned to their normal lives.

Descending into Paama airfield the next day, the blue skies of the South Pacific gave way to rain showers, which spattered onto the windscreen of the little plane. Even by Vanuatu standards, Paama is a small and dark island. Its scenery is blackly volcanic, and its people have a reputation for sorcery. Beyond the gloomy, wet hillsides of Paama loomed the neighbouring island of Lopevi, a monstrous mile-high volcanic cone. Earlier this year a local chief failed to perform a ritual designed to appease Lopevi, and since then the mountain had been fuming, rumbling the earth and belching clouds of ash that blow onto Paama.

Dark green vegetation thrives in the nutritious ash, but machinery does not; the only vehicle on Paama broke down years ago. Since then the main road had fallen into disuse, and been reclaimed by the forest. No boats were around, so the only way to get from the airfield into the village was to walk along the beach. One of the gap girls met me at the airfield, and showed me the way. For a mile or two we trudged through volcanic sand the colour of asphalt, and clambered across piles of black boulders. Staggering dangerously under the weight of my rucksack, I began to regret all of the things I had bought in Port Vila.

Eventually, after clambering around a particularly rocky headland, the steep coastline opened out into a grassy cove, and we arrived at Liro. This was Paama's main village - built around a Presbyterian church established a century ago by Maurice and Jean Frater, two Scottish missionaries. (Their grandson, Alexander Frater, wrote about Paama in his entertaining book of tropical travels, Tales from the Torrid Zone.)

I introduced myself to the villagers I met - who were friendly and curious to know why I had come to their little island - and a small boy was sent off to find Kenneth, the village chief. (In a society without mobile phones and text messaging, small boys are frequently used as a substitute.)

For once I'd succeeded in telephoning ahead before arriving in a village, so Kenneth was expecting me. He showed me the way to his guesthouse, a lovely thatched building with walls woven from faded bamboo. (Nearly everything in Liro looked old and faded.) He gratefully took the daily newspaper that I'd brought from Vila, and invited me to join him that evening for kava drinking.

The gap volunteers and I cooled off that afternoon by going for a swim, but didn't venture far out to sea. Paama's waters are notoriously shark-infested (the island is home to sorcerers who transform themselves into sharks to devour their enemies), and the sooty sand provides the beasts with excellent camouflage. Although it was early afternoon on a tropical beach, the sheer darkness of the scenery was overpowering. The looming craters of neighbouring Ambrym, a giant slumbering dinosaur of an island, imposed themselves the horizon. Men fishing from distant canoes were like silhouettes in a painting. Looking down through the water, my arms and legs looked like those of an exhumed corpse - green-tinged and pale against the coal-black seabed. On the shoreline behind us, the little wooden cottages and concrete schoolhouses of the village were faded and grey.

While the volunteers showed me around Liro, I chatted to them about their placement. It turned out that things were not well. White girls were a new phenomenon on Paama, and the volunteers had found themselves menaced at night by 'creepers', sinister men who would lurk under their windows, peer through the cracks in the walls, and try to force entry through shuttered windows that couldn't be properly secured.

There were other issues too. The school bursar was absent, and the village's little bank was closed (the person with the keys had gone away), leaving the girls short of money with which to buy food. Their responsibilities at the school had never been made clear, and their timetables altered from week to week as colleagues changed their minds about which classes the gap volunteers should be teaching. Their school lacked even the most basic resources - there is money to buy equipment, I was told, but the teachers spend it on themselves.

Meanwhile, the school headmistress - who should have sorted all these problems out - had gone away leaving nobody in particular in charge. Even when she is around, she appears to care about nothing at the school except her salary. The reason that the useless woman has yet to be sacked became clear when I saw posters on the walls depicting a prominent Vanuatu politician. He and the headmistress shared a surname.

The Five Horseshoes kava bar on Paama

Over peppery-tasting shells of kava at the Five Horseshoes, a lamp-lit thatched hut that looked the perfect picture of a fairy-tale tavern (its name had been bestowed on it by a previous British visitor), we discussed all these problems with Kenneth the chief. He offered to call a meeting of the villagers and put a stop to the creeping. Don't worry, he told the girls: if any man rapes you, you will get many mat and pigs in compensation. This last comment didn't have the reassuring effect that the chief had hoped, but his meeting with the villagers seemed to have an impact; the creeping stopped.

There is something hauntingly old-fashioned about Liro. The place has a sense of Sleepy Hollow or The Village about it. It felt like the ghost of a Scottish community from a century or two ago, perhaps the kind of community that the Fraters left behind.

The atmosphere was created partly by the damp clouds that billowed continuously over the mountain. Rain dripped from the thatched eaves of the guesthouse in which I was staying, and sluiced off the tin roof of the outhouse into a nearby tank. There was no electricity in Liro that week; the generator had run out of fuel. At night I went to bed by candlelight, then lay in the dark listening to the scuttling of rats in the thatch and the silence of the ghosts outside. (A local story tells how the world's creatures were originally created on Paama, and later expelled from the island - all except for the rats, which got left behind.)

At dawn, I got up and boiled tea and porridge on a gas stove, using water fetched in a tin jug from the tank. The girls joined me: at their own house the bottle of cooking gas had run out, and nobody at the school was willing to replace it.

From nearby, we could hear children chanting hymns in Paamese. It sounded distantly like Gaelic. Recently, the language was under threat from Bislama, but the islanders have since begun to actively teach Paamese to their children, and a project is underway to translate the Bible into the language. A ceremony will be held next month to mark the completion of the first book to be translated, the Gospel of Mark. Matthew, Luke and John will follow.

Since flights only land on Paama twice a week, I had three days to spend on the island. Fortunately, Liro is a friendly and hospitable place, in spite of its ghostliness, and by the end of my visit I felt like part of the community. I got to know the shopkeepers, the church minister, the chief and his wife, and the local aid workers. I chatted in English to the children at the school, and in Bislama to their teachers. I met a former student of mine - a girl who was in my Year 11 Economics class back in 2001, who is now working as a science teacher on Paama. I learned more Paamese during my three days on the island than I have ever known of Gaelic, and I reflected afterwards that I ought to have made more effort during the two years I spent in the Scottish Highlands.

While on Paama, I was invited to the Father's Day church service (held at the end of September here) at which men dressed in their Sunday best were showered with confetti and talcum powder by appreciative women and children. (Despite protesting light-heartedly that I wasn't anybody's father, I was given the same treatment.) After the service, there was cake, and a big celebratory lunch for the entire village. I talked to the church minister, a middle-aged man who had been born on Lopevi in the days before the volcano's increasingly-vicious eruptions rendered the island uninhabitable.

On my last day, as I made my way back to the airfield and Liro disappeared behind the headland, the clouds dispersed and blue morning light flooded the beach. The ghosts faded, and Paama became a mere tropical island - sun-sparkled waves washing against a coconut-fringed shoreline.

Flying away from Paama, with Lopevi behind

It took no less than seven short flights - ranging from five to twenty minutes in length - to get from Paama back to Pentecost. The plane first touched down at the eastern end of Ambrym Island, then landed again at the western tip of the island, skirting the monstrous volcanoes in between and providing cloudy glimpses of scenery in which the dinosaurs would have looked quite at home. The next stop was Norsup on Malekula Island, which I visited five years ago, when a fire had recently reduced the terminal building to a burned-out shell. Nobody had rebuilt it yet: it was still a burned out shell.

The next airport, by contrast, had recently been renovated, and now boasted a vast, hangar-like terminal building and a wide, tarmacked runway. This was "Pekoa International Airport" (the government is currently in the process of trying to persuade international flights to actually land there), the gateway to Espiritu Santo, Vanuatu's largest island, and Luganville, its major northern town.

Santo - as both the island and the town are generally known - is sprawling, sleepy, and thoroughly dilapidated. Having a few hours to spare in between planes, I caught a bus into town. (Actually, it was a taxi that agreed to take me for the price of a bus fare, since the giant airport was virtually deserted and the driver knew that his chances of picking up another customer were slim.)

In the last five years, Santo hadn't changed as much as I'd hoped.

Whilst Liro (civilised by Scottish missionaries) feels like the ghost of rural Scotland in the 1900s, Santo (established as an American base during the Second World War) feels like the ghost of small-town America in the 1940s. The town has been slowly decaying ever since the Americans abandoned it at the end of the war, and since my last visit an additional five years' worth of cracks and corrosion had been added. A few colourful buildings had received a lick of paint - mostly government offices, and hotels and tour operators catering for the visitors who come to dive on wartime wrecks - but the rest were as white and faded as ever.

Nowadays, Santo fulfils the same role in Vanuatu that Glasgow does in Scotland. Both are second towns, unable to compete with the capital for wealth and status, and ugly and neglected in consequence. However, both remain major population centres (in Vanuatu, twenty thousand inhabitants is more than enough to qualify as a major population centre) and continue to attract young people because they contain useful amenities that are absent in more rural areas. Santo, like Glasgow, is a place people come to when they want to go shopping or get drunk.

I visited the shops, stocked up on yet more food to take back to Pentecost (replacing some of the supplies I'd shared with the girls on Paama), and wandered along Main Street in search of something interesting to do. Failing to find anything, I walked all the way back to the airport.

There were only three people on the 8-seater plane that took me back to Pentecost: myself, the pilot, and a boy returning to school after the holidays. I realised that if anything happened to the pilot, I would be the one who would have to try and land the plane safely. I didn't fancy my chances.

On its way back to Pentecost, the plane touched down at West and East Ambae. At West Ambae, a big hand stuck itself through the door of the plane and shook mine. It was Graham Bule, the Principal at Londua, who was at the airfield seeing off his daughter, who was returning to Ranwadi after the holidays. (Term had officially begun two and a half weeks ago, but the students were still drifting back.)

It had rained heavily on Pentecost the previous day. The river running alongside Lonorore Airfield was too high for a truck to drive through, so we had to wade across the river (hauling our luggage, and half a dozen other boxes marked "Ranwadi" that had arrived on the plane). A truck was waiting on the other side (not the school truck, which had broken down, but one belonging to a man from Waterfall Village, which had been hired to take us back to Ranwadi).

Attempting to cross a second raging river, the truck stuck a big stone in the middle of the river and stuck fast. It took the help of about a dozen passers-by, standing waist-deep in the rushing water and shoving stones or pushing on the obstinate vehicle, to extricate the truck from the river.

If only there was a bridge

I returned to Ranwadi to find the school in the grip of a health scare.

A rumour had gone around that somebody at Ranwadi had AIDS. Bullying children, with no evidence on which to base their suspicions, had already pointed the finger at one unfortunate classmate, who had run away from school. Parents of other students were phoning up and demanding that their children be sent home. It wasn't safe for them, they said - not if there's AIDS at Ranwadi.

Among the teachers, fingers were also being pointed. Who did this story come from? Is it true? Did somebody tell the students that there's AIDS at Ranwadi?

It emerged that the story had been started by a teacher, acting on information allegedly given to him by a friend working at a clinic. He had stood up at breakfast time and announced to the students that somebody among them had AIDS, but refused to say who. Paranoia had ensued.

The next morning, the Principal and I gave speeches of our own at breakfast time, and tried to calm things down. As a biology teacher I talked to the students about the virus, explained that being HIV positive is not technically the same thing as having AIDS, and pointed out that unless the students are sleeping around or using dirty needles they should have little to fear from the disease, even if somebody at Ranwadi is infected. The Principal sternly reminded the students that it is un-Christian to make such accusations about people, regardless of the circumstances.

The panic died down, but the fear remained. Students and villagers told wild stories: in Port Vila, 70% of all students had AIDS, and people were going around stealing syringes of infected blood from clinics and stabbing strangers with them in the dark. I told them I didn't believe a word of it. According to the last reliable information I'd heard, there had only ever been three confirmed cases of HIV in the whole of Vanuatu. When I had been in Vila a week ago, the newspapers contained no mention whatsoever of AIDS. Ah, but the situation has changed, people told me. I thought this unlikely, but since there was no way I could actually disprove it (Pentecost is beyond the reach of newspapers or local radio, and the telephone lines were down so I couldn't search the Internet), my opinion was dismissed.

Don't try too hard to squash the rumours, some of my colleagues advised me. AIDS may not yet be a big problem in Vanuatu, but it soon will be unless people learn to take precautions. It's good that people are afraid.

They may have a point, but it worries me that AIDS education in Vanuatu will suffer the same problem as the boy who cried wolf, or the teachers who tell children that smoking spliffs will destroy their health. People will be frightened at first, but when people realise that the worst of the stories are untrue, they will become blasé, and overlook the fact that there is a genuine risk.